The history, development and growth of the Airline Industry

The airline industry was born with an 18-mile flight in 1914, where passengers paid $5 – or roughly $120 in 2017 dollars – for transport between St. Petersburg and Tampa, FL.[i] The Kelley Act of 1925 gave the biggest boost to the airline industry, which for the first time allowed private aircraft to deliver U.S. mail. Airlines were granted authority on delivery routes based on their bids, and while some passenger services did exist, they were not the key revenue generating activities of the airlines.

During the Great Depression, Congress was concerned about the stability of the airline industry, and viewed it as necessary for the nation’s economic development.v This led to the enactment of the Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938.

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) had authority to regulate entry, mergers, fares and structures, and subsidies.[ii] When air carriers wanted to take on new interstate routes or change prices, they went through the CAB. Despite receiving 150 requests for new long-distance routes from different airline operators between 1938 and 1978, the CAB denied every application[iii]. As a result, the only viable path to growth for most airlines was to access new routes via mergers, which created an oligopoly of a few large players.

The ability to raise top-line revenue was limited, so airlines looked for ways to compete and increase profitability through cost savings. Delta recognized the difficulty in efficiently serving passengers spread out across sparsely-populated areas, and in 1955, created the first hub-and-spoke network. By locating a hub in a densely-populated city, an airline could combine connecting passengers with direct passengers, resulting in production efficiencies of fewer empty seats on each flight. This resulted in higher aircraft utilization, and spread the fixed costs across a broader passenger base. A strong hub presence allowed the airlines to operate flights between a greater number of cities with more frequent flights between city pairs. Coupling these benefits with the limited resources of airports, gates, and landing rights, carriers with dominance at a hub airport gained a degree of monopoly power.[iv]

Regulation was hotly debated for nearly a decade, and in 1978, Congress passed the Airline Deregulation Act, which gradually phased out the CAB through 1985.

The liberalization of entry allowed a wave of new airlines, and fierce competition resulted. Fare wars were frequent, and although the wave of new entrants accounted for less than 5% of the domestic market, their lower costs allowed for increased pressure on price. This, coupled with the recession of the early 80s, resulted in more than 150 bankruptcies and 50 mergers and the creation of an oligopoly where the eight largest airlines dominated 94% of the market.[v]

With fewer players in the market, airfares increased significantly. Clever price signaling strategies, wherein a carrier would pre-announce fare increases and watch for competitor response, resulted in airfare hikes through the early 1990s, eventually resulting in a DOJ investigation and settlements of $500 million.[vi]

Following 9/11/2001, many passengers were wary of air travel and the result was a dramatic decrease in ticket demand. The Aviation and Transportation Security Act of 2001 also brought new security requirements, such as reinforced cockpit doors and increased passenger and baggage screening, the costs of which were borne by the industry.

Congress attempted to prop up the industry with $5 billion in grants and $10 billion in loan guarantees as well as reimbursements to airlines for security costs. Despite these efforts, with rising fuel prices, airline profits tumbled in the early 2000s.i

With the cost of fuel being one of the most significant and volatile expenses for airlines, low-cost carrier Southwest Airlines was the first to tackle this volatility with fuel hedging.[vii] Since that time, other airlines have followed suit and also focused on operating more fuel-efficient aircraft. In 2012 Delta took an even more ambitious approach by vertically integrating with the purchasing a refinery.xii

Delta Air Lines History

In 1929, Delta operated its first passenger flight carrying five passengers and one pilot[viii]. Throughout the 1930s, Delta’s main revenue generator was the mail service, with passenger flights generating only supplemental revenue.

Delta continued to grow its passenger service into the 40s, relocating its headquarters to Atlanta, GA, where it is still located today. The largest single hub in the world and one of the industry’s greatest assets, Delta’s control of the Atlanta hub is a key source of competitive advantage.xv In 1945, C.E. Woolman was named President, a position he held until 1965 when he was named Delta’s first CEO and Chairman until his death in 1966. Woolman is credited with having built the culture centered around employee engagement, a large contributor to its success. This culture continued until the 1990s, when the airline met difficult times under Ron Allen.

Under CEO Leo Mullin, Delta created a management culture that demanded the best of everything, despite warning signs that cost-cutting was needed. Mullin was credited with negotiating a labor contract in 2001 that paid top pilots an unprecedented salary of $300,000/year. Delta’s credit rating fell, and it was placed on a credit watchlist. After pressure from Congress, and a union unwilling to renegotiate, he stepped down in 2004. In 2005, Delta joined Northwest, United Airlines, and US Airways in Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

When Delta entered bankruptcy, it’s Revenue per Available Seat Mile (RASM) was 86% of the industry average. Delta focused inward, to restructure, cut costs, and recreate itself and its brand. Upon emerging from bankruptcy two years later, its RASM was up to 96% of the industry average. By 2014, it led the industry, with RASM reaching 107% of the industry average[ix].

This RASM effectiveness lead Delta to be the net most profitable airline in the US market with an average 9% revenue premium. As of Q3 2017 Delta surpassed the previously most profitable airline in the world, American Airlines, by $2B.

SWOT analysis

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

| Internal | – Scale – 2nd largest airline in the world – Regional networks, hubs – World’s largest hub, Atlanta – Vertically-integrated fuel supply line – Organizational culture, controls – Premium brand – Partnerships: international and credit cards – Low unionization | – Costs per ASM (Available Seat Mile) – Information Systems outage history – Lower customer service ratings when compared to international carriers (Skytrax #32 rating) |

| Opportunities | Threats | |

| External | – More fuel-efficient planes – Increased technology innovations – Product differentiation: hard product, customer experience | – Future regulatory environment – Competition – Fuel prices – Geopolitical / Security events – Business travel alternatives (i.e. Skype, WebEx, others) |

Delta’s strengths and weaknesses

Shortly after emerging from bankruptcy, Richard Anderson shepherded Delta to become one of the most profitable and well-run airlines. Delta made deliberate strategic decisions to become a different airline, with a focus was on the customer flying experience. Its goals were to add scale, expand its geographic area by merging with another U.S. carrier, and grow internationally by partnering with foreign airlines.

In 2008, Delta Air Lines merged with Northwest Airlines Inc. making it the world’s biggest airline. Delta’s M&A team was deliberate about evaluating potential opportunities that would complement Delta’s current network assets. The merger with Northwest provided those complements as Delta’s strength had been in the South, while Northwest operations were based in Minneapolis and Detroit. Completing this merger ahead of the competition’s mergers allowed Delta to improve operations before rivals.

Continuing to expand its market, Delta took equity stakes in leading Brazilian, Mexican, and European carriers, and most recently, Korean Air. Although regulations prevent cross-border mergers, Delta’s relationship with these carriers creates a truly global network, allowing Delta to cover markets comprising 98% of US passengers’ international travel demand xxxv andfeeding more travelers into Delta’s highly-efficient network, a key aspect of the airline’s strategic focus. Delta also used this approach domestically, most notably with Alaska Airlines. As the market began to peak in 2015 and 2016, both airlines began to expand their domestic network capacity, leading to head-to-head competition, especially on routes between Seattle and California, resulting in dissolution of the partnership in 2017.

Perhaps Delta’s most dramatic acquisition came in 2012 with the purchase of the Trainer oil refinery. With oil prices rising, Delta decided to vertically integrate, providing an average cost savings of five- to ten- cents per gallon over the industry average.[x]

Delta knew that improving processes wasn’t enough, and that strengthening culture and pursuing more-innovative strategies was essential. This guided them to “Rules of the Road” guiding principles.[xi] These principles – honesty, integrity, respect, perseverance, servant leadership – foster inclusiveness and teamwork. The corporate culture discourages employees from joining unions, and the work force (the only major airline outside the Middle East that is non-unionized) has rejected nine proposals to unionize.

Delta provides employee incentives unique to the airline industry, such as profit sharing, stock ownership, and raises despite financial crisis and spiking fuel prices. The profit sharing program allocates 10% of earnings before taxes and management compensation in bonuses. The employee stock ownership plan gives pilots, flight attendants, ground crew, and support staff 15% of company’s equity. Management compensation is low for similarly-sized companies, and benefits and retirement plans are the same for all employees, executives and ground crew alike.[xii]

Delta’s SkyMiles loyalty program, in partnership with American Express, is a key strength. The companies have a long-term agreement for a cobranded credit card that is a revenue generator for both companies. Agreements such as these involve selling miles to banks, who then award them to customers for future redemption. Delta generated $2.7B in revenue from this arrangement in 2016, and expects growth of about $300M/year through the term of the current agreement until 2022.

One of the most public weaknesses, disruptions in Delta’s IT networks in 2016 and 2017 negatively impacted the company, causing system failures and the cancellation of many flights.

The nature of the external environment surrounding the company

By 2017 the United States airline industry produced record performance, generating 13 consecutive quarters of profitability with operating margins near or above 10%. xxxvi In an industry long-characterized by large losses and repeated bankruptcies, this 15-year high for the industry is due in part to more-disciplined management, but more significantly to favorable market cost conditions.

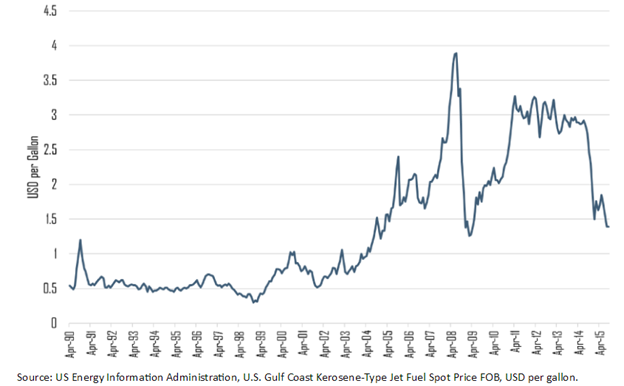

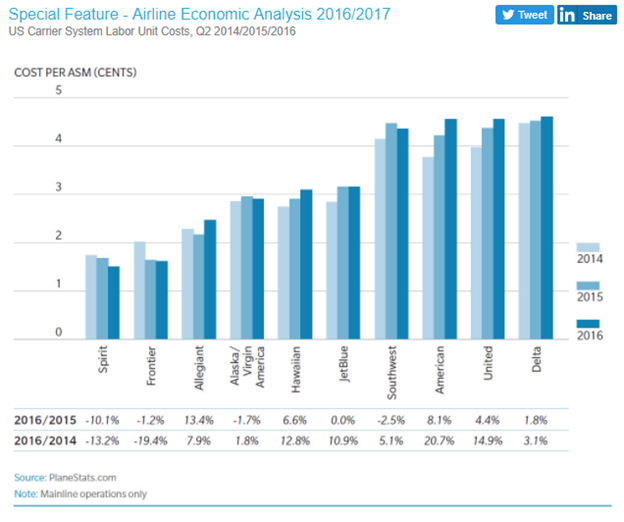

After weathering high fuel costs in the mid-2000’s (Jet Fuel Prices Graph Below), many carriers aggressively focused on cost savings in two key areas: retirement of older, less fuel-efficient aircraft and negotiations of price savings from major labor unions. This effectively created a favorable price ceiling for labor costs across the industry.

The dramatic drop in fuel prices in mid-2014 in combination with cost-saving measures provided domestic airlines with record profits for 2014, 2015, and 2016. However, these conditions threaten to push them back into the price and capacity wars of years ago, with too much capacity coming online at discount prices and the economy still growing in the low single digits. This trend has been particularly acute with routes in the US, where both legacy major carriers and value carriers have been aggressively expanding.

Many key cost categories have already begun to increase and are likely to continue in coming quarters, including labor and jet fuel prices.

Substitutes

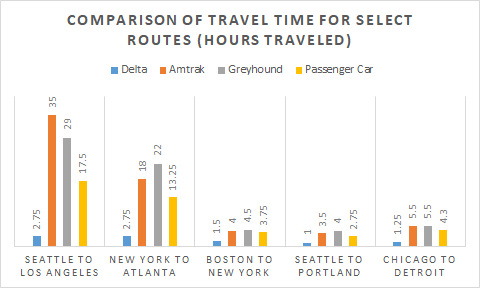

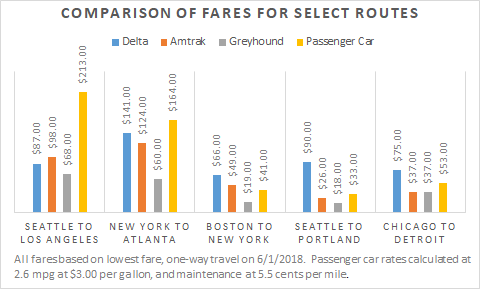

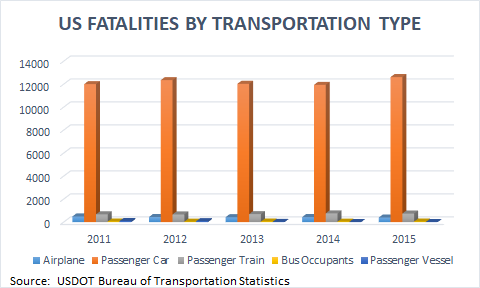

When evaluating substitutes, costs, travel time and safety are key factors. Airline travel requires less time on certain routes (Graph B); however, the costs for airfare are significantly higher for these segments. For long-distance routes, there is an advantage in air travel when comparing time traveled and cost per ticket (Graph C). Not only is the travel time significantly lower for airline travel, but the cost is comparable or lower than substitutes, and air travel is notably safer than passenger cars (Graph D).

As an inexpensive alternative to business travel, virtual meetings have become popular with the emergence of tools like Skype and GoToMeeting. Business travelers account for 12% of passengers, but are typically twice as profitable for airlines. On some flights, business passengers represent 75 percent of an airline’s profits,[xiii] meaning greater competition for the business traveler than other market segments. Thus, airlines are upgrading their cabins to include more business class seats that recline fully and flat-bed seats.

Competition

Over the past decade a wave of mergers has reduced the number of large US airlines from nine to four, and resulted in the four biggest carriers gaining control of 80% of the market, compared to just 48% a decade ago. By comparison, in Europe the top four carriers control ~45% of the market. Analysis by the Associated Press in 2016 found that during this period of consolidation, average domestic airfares rose by 5% after adjusting for inflation.

Mergers have altered the competitive landscape to the benefit of the airlines, resulting in a combination of high fares and poor service due to a lack of competition. U.S. policy makers allowed multiple mergers that resulted in a single carrier accounting for more than half of capacity at 40 of the 100 biggest hubs.

The standards of service are lower for domestic carriers as rated by the widely used Skytrax airline ranking. There are no U.S.-based airlines in the world’s 30 best carriers, compared with 9 from Europe. The highest ranked U.S. airline is Delta at 32.

Barriers to Entry/Exit

In the years following deregulation (1982-1996) approximately 80 new airlines entered the U.S. market, despite the high barriers of fixed capital, with the three largest costs to airlines being aircraft, fuel, and labor.i

The exit barriers in the U.S. also remain high. Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection has allowed many airlines to continue to operate when the economics dictated exit from the market. In 2005, 50% of flights in the US were operated by firms that were currently or recently in bankruptcy protection.xxii

While current regulations are narrower in scope and “bite” compared to pre-deregulation, they are a severe administrative burden to a new entrant. The FAA regulates fitness of equipment, certification of flight personnel, operating procedures, and still grants air carrier’s authority to operate. Another critical input to a carrier’s success is accessing and negotiating airport gate space. Delta’s size and tenure provide the knowledge and expertise to navigate the regulatory environment and absorb the administrative costs across its operation.

Customer switching costs are low with the pricing transparency available on the internet, though ~30% of customers select a fare that is not the lowest priced.xxii Indeed, frequent flyer programs create a level of brand – or at least network – loyalty, as passengers may opt for a higher fare or additional segments for elite status or miles on their preferred carrier’s network.

Fleet Upgrades

With fuel efficiency representing as much as 33% of an airlines operating costs, an opportunity exists to increase profitability by going after more fuel-efficient aircraft. The Boeing 737-MAX 9, for example, has reduced fuel consumption by 14% over its predecessor.[xiv] Technological advances that leverage new design styles, more efficient engines, and advanced materials[xv]–[xvi] have the potential for substantial fuel savings.

Threats

Terrorist, geopolitical or security events could have a huge impact on the business, as demonstrated across the industry post 9-11. International conflicts outside the US could still result in additional costs through loss of markets or having to fly around certain areas deemed riskier, such as Ukraine.

Despite the move to more fuel-efficient aircraft, the industry is heavily dependent on the price of aviation fuel. Although Delta is the only airline to own a refinery, outside of hedging, itself inherently risky, this does not protect them from volatility in oil prices which have risen significantly in the past year.

Labor-related industrial action could result in disruptions at hub or key airports and have an adverse impact on Delta operations. Delta, of the three legacy carriers, has a significantly lower rate of unionized workers at approximately 19%, presenting less of a risk than competitors.

New or altered federal regulations present a threat to the industry as they pose surprising new costs, taxes, rules to entry and exit, and other hurdles to competition.

Although the legacy three have been consolidating around hubs, the availability of more fuel-efficient aircraft with longer ranges is opening previously unprofitable point-to-point routes for the lower cost carriers that may challenge the hub and spoke model favored by Delta. The hubs could be further threatened by the opening of nearby commercial airports such as a new commercial airfield at Paulding County near Atlanta.

Overall Corporate and Business Level Strategy

“Setting the standard as America’s best run airline which redefines the flight experience,” is the often-stated direction of former CEO Richard Anderson, which continues with current CEO Ed Bastian. This strategic ethos guided Delta from a 2005 bankruptcy to record profits in 2016.

Beginning with C.E. Woolman in the 1930s, Delta embraced a conservative approach and family-style company structure, with leadership acting as a wise, benevolent father figure.[xvii] This culture continued with Woolman’s successors. In 1974, Delta significantly reduced its scheduled departures, grounding 22 planes, yet never laid off an employee or reduced pay. Then CEO W.T. Beebe attributed Delta’s engaged staff to the open and honest communication within the company, including a policy to answer all questions. “Call it trite if you want to, but it works. We don’t try to keep unions away. We just take care of our people.”[xviii] In 1982, when the recession was taking a toll on all airlines, Delta posted its first loss after a consecutive 35 years of profitability. Three flight attendants took it upon themselves to launch a fundraising campaign to pay for Delta’s first 767, raising $30 million from current and former employees[xix].

Delta deviated from the paternal leadership structure with CEO Ron Allen in 1987. Described as a young, aggressive risk-taker, Allen’s ambition to grow Delta’s international presence caused the company to suffer significant losses. In 1991, Delta laid off unionized staff, cut wages for non-union staff, and cut 6000 jobs through early retirement, attrition, and elimination of part-time roles. This continued with another round of massive cuts in 1994, making employees feel betrayed and losing the familial ties they once felt with leadership. This had widespread negative impacts to operational effectiveness and customer service opinions.

When CEO Leo Mullin took the helm in 1997, he reversed many of the actions of his predecessors, which boosted morale; however, he lost the cautious conservatism that was so inherent in the company’s history, and his overly “generous” approach backfired when he was forced to backtrack on many of his promises.

When Mullin stepped down, CEO Gerald Grinstein immediately set about repairing the damage. Grinstein recognized that the company needed to restore the “we’re all in this together” mentality. He capped executive salaries, eliminated his own bonus and stock options, cut 41% from the executive compensation plan, and made an edict that only when workers were restored to industry-average salaries would executives see salary increases. He then created an equity plan, allocation of funds for raises and bonuses, and profit-sharing plan. This swift and aggressive movement largely restored the trust and sense of partnership that had been damaged by his predecessors. xix

Delta’s largest stumbling block has been misalignment between executive leadership and its workforce, which historically has been one of its biggest advantages. The recent realignment was a key part of the return to profitability, resulting in engaged employees and by extension satisfied customers.

Organizational Alignment and Strategy

Delta’s commitment to its culture is in alignment with its strategy. Delta considers culture to be its greatest competitive advantage, and it highlights this with employee incentives that are unique to the airline industry. Employee engagement scores are at an all-time high, which has brought them numerous accolades.

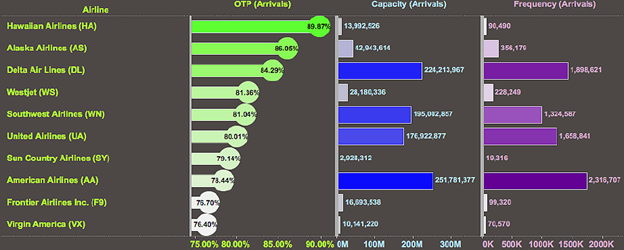

Delta’s employee engagement improves customer experience, which ties directly to business and performance results, as can be seen in industry standings (Graph E). The non-union employees are often able to turn five planes in the time other airlines turn three.xix Delta proudly touts its generous employee compensation, and while there’s no labor cost advantage, this culture contributes strategic benefits in terms of employee-driven continuous improvements to operational efficiencies and customer service.

Recommendations

Delta should “Keep Climbing.” Delta continues to innovate and its approach to cabin segmentation, product differentiation, and excellent customer service have been key to its success, positioning the carrier for continued profits. Delta should continue to leverage its brand and drive a price premium while remaining price competitive. Delta should use caution in its approach with the low-cost segment, as there is risk of erosion of the premium brand perception, which could impact the premium price.

Delta has made and is in the process of making some long-term strategic investments in fuel supply, operational efficiencies and organizational controls to ensure future profitably. Delta should also consider further investment in IT and digital customer experience. Delta’s recent IT outages in 2016 and 2017 grounded hundreds of flights and damaged their brand. Delta has an opportunity to be a market leader from a technology perspective and deliver compelling best-in-class customer experiences, facilitated by technology.

Going into 2018, Delta will need to continue to carefully manage a capacity environment which is being re-sized and continue to make wise investment decisions to differentiate products and improve customer experience to capture market share. Aggressive fleet renewal to replace older aircraft with more efficient fleet types in 2018 and beyond is vital for both maintaining a strong unit revenue trajectory and keeping costs in check to achieve its profit goals. Fleet renewal is the company’s most important initiative in that regard. Delta is among the most profitable of US airlines, and the company should maintain its discipline, continue to control costs, and continue operational and customer service excellence that drives frequent flyer’s loyalty and allows them to command a premium. The company must keep sight of what has driven its nearly-century-long success: outstanding customer service, the best workforce, and exceptional leadership.

[i] Sturm, R.S. “A Financial History and Analysis of the U.S. Airline Industry,” Airline industry: strategies, operations and safety, Connor R. Walsh, ed, Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2011

[ii] Borenstein & Rose (Book chapter “How airlines work… or do they” from “Economic Regulations in the Airline industry)

[iii] Edelman, R., & Baker, B. The impact of implementing the airline deregulation act on stock returns. Journal of Economics and Finance, 20(1), 79-99 (1996).

[iv] Nero, G., “A note on the competitive advantage of large hub-and-spoke networks,” Tranportation Research Part E, 35, 225-239 (1999).

[v] Dempsey, P.S., “Robber Barons in the Cockpit: The Airline Industry in Turbulent Skies,” Transportation Law Journal, vol. 18, no. 2 (1990).

[vi] Financial Condition and Product Market Cooperation, https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2014/201463/201463pap.pdf

[vii] Manuela Jr., W.S. et al “An analysis of Delta Air Lines’ oil refinery acquisition,” Research in Transportation Economics 56 (2016).

[viii] “Delta Leaders: C.E. Woolman,” accessed 11/20/2017 at http://www.deltamuseum.org/exhibits/delta-history/leaders http://www.deltamuseum.org/exhibits/delta-history/leaders http://www.deltamuseum.org/exhibits/delta-history/leaders http://www.deltamuseum.org/exhibits/delta-

[ix] Reed, T., “How Delta Air Lines Mapped A Path To Success And Followed It,” Forbes Online, 10 May 2014 (accessed 24 November 2017 at https://www.forbes.com/sites/tedreed/2014/05/10/how-delta-airlines-mapped-a-path-to-success-and-followed-it/)

OAG Aviation Worldwide Limited, “OAG Punctuality League – Annual on-time performance results for airlines and airports”, Published January 2017. (accessed November 27, 2017 at http://www.oag.cn/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PunctualityReport2016.pdf )

[x] Anderson, Richard H. (December 2014) “Delta’s CEO on Using Innovative Thinking to Revive a Bankrupt Airline” Harvard Business Review https://hbr.org/2014/12/deltas-ceo-on-using-innovative-thinking-to-revive-a-bankrupt-airline

[xi] Delta Air Lines website http://bedeltabedifferent.com/the-delta-difference/

[xii] Anderson, Richard H. (December 2014) “Delta’s CEO on Using Innovative Thinking to Revive a Bankrupt Airline” Harvard Business Review https://hbr.org/2014/12/deltas-ceo-on-using-innovative-thinking-to-revive-a-bankrupt-airline

[xiii] Investopedia (April 13, 2015). “How much revenue in the airline industry comes from business travelers compared to leisure travelers?” https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/041315/how-much-revenue-airline-industry-comes-business-travelers-compared-leisure-travelers.asp

[xiv] Hethcock, B. “How the Boeing 737 MAX will cut costs and open new routes for Southwest Airlines,” Dallas Business Journal, 01/18/2017.

[xv] “X-48 Research:All Good Things Must Come to An End”, Nasa Aeronautics News, 04/16/2013, accessed 12/01/2017 at https://www.nasa.gov/topics/aeronautics/features/X-48_research_ends.html

[xvi] Press Release “Aurora D8 takes next step towards X-Plane” 09/13/2016, accessed 30 November at https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/aurora-d8-takes-next-step-towards-x-plane-300327183.htmlhttps://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/aurora-d8-takes-next-step-towards-x-plane-300327183.html

[xvii] Kaufman, B. “Keeping the Commitment Model in the Air during Turbulent Times: Employee Involvement at Delta Air Lines,” Industrial Relations Vol. 52, No. S1 (2013)

[xviii] Bedingfield, R.E., “Labor is Delta’s Key to Profits,” New York Times, 04/28/1974.

[xix] “Aircraft: Boeing 767 the Spirit of Delta” at the Delta Museum, accessed 11/29/17 at http://www.deltamuseum.org/exhibits/exhibits/aircraft/b-767-the-spirit-of-delta

Recent Comments